|

Five Executive Follies

How commodification imperils compassion in personal healthcare

David

Zigmond

©

2011

Summary: Commodification, competition

and commercialisation are often introduced as agents of efficiency into State welfare services. In healthcare all

of these may, unwittingly, lead to a loss of ‘soft skills’; personal understanding and compassion. The human and

economic cost is considerable. How this happens is not obvious. This article explains.

Prologue

The threat to healthcare from inadequate resources or management has become a little-challenged truism: easy to

understand and demonstrate. Healthcare is now submissive to our Management Culture: a world which then authoritatively

delegates all human problems to specialists and their executive actions. All this can seem simple, sensible and

correct.

The reality is more complex. Paradoxically, there is an additional

and opposing, though less obvious, threat to our healthcare: an excess of such management, specialist activities and resources – but misplaced. This more subtle and countercultural

reality is – it is proposed here – responsible for much of our current system’s incapacity to imaginatively address

individual variation. Such obliviousness to human diversity and complexity has serious consequences. The more stark

examples of failures of physical care make headlines that are hard to understand or even believe. In contrast,

failures of personal understanding, and thus therapeutic and compassionate engagement, are usually born invisibly,

painfully and privately. Such are the perils of abdicating our capacity to conceive or care more holistically.

Compassion becomes an inevitable casualty when our personal attunement

or engagement are compromised. The word ‘compassion’ derives its meaning from a Latin root ‘to suffer together’,

thus offering a ‘transpersonal’ psychology; one drawing from exchanges of resonance and imagination. This is often

very different from distancing 'objective' psychologies used unilaterally by healthcare professionals to pathologise,

categorise and commodify in attempts to tightly manage healthcare. Yet there are many studies showing how an empathic

bond conveying compassion is a powerful source of comfort and healing for the sufferer, and work-satisfaction (and

healing) for the healer.

The skilled evocation of compassion often has powerful effects, but

is a subtle activity. This was well recognised and explored by previous generations of practitioners. It now ails

amidst hardy slogans of 'Increased Patient Choice' and 'Ensuring quality of care is always central'. How could

this come about?

The causal paradoxes and anomalies have been poorly recognised and

understood. What follows dissects and explores.

Five Executive

Follies:

How commodification imperils compassion in personal healthcare

_______________________________________

The fatal metaphor of progress, which means leaving

things behind us, has utterly obscured the real idea of growth, which means leaving things inside us.

GK Chesterton

Fancies versus Fads, 1923

We are living longer, more complex lives. Our technological possibilities multiply. Inevitably healthcare expectations,

then demands, burgeon. To manage all this, an Industrial Revolution has been unleashed in the NHS. This revolution

is itself guided by a core phalanx of doctrines. These are independent of other political considerations or affiliations,

and implicitly embraced by all. Such assumptions have developed from cultural changes rooted in our advanced industrialised

ways of life. These predicate often unconscious values and mind-sets. Consequently, our rubric for healthcare has

become increasingly of applied sciences, leaving humanities peripheral and disregarded. The tasks then become reduced to engineering

tissues or behaviours, rather than extension to nurturing human understanding and contact.

The doctrines that flow from such assumed applied science and industrialisation may thus offer real help in discretion,

but an added tranche of folly in excess. Like many truisms, they turn specious, then hazardous. The Law of Unintended

Consequences becomes evident: industrialising healthcare, much to our perplexity, is responsible for very substantial

'collateral damage'. Despite allocating ever-increasing resources, in certain areas, our therapeutic and compassionate

engagement is poorer. The progressive loss of quality and continuity of personal contact — essential elements of

compassion — are crucial factors. This brief survey samples how these difficulties constellate.

Below are itemised these interlocking cardinal notions. Consequences of their over-use are portrayed. In the final

section, authentic vignettes illustrate how these Five Executive Follies converge; what happens to our care.

Failure to accurately conceive the essential nature and limitations of the medical model is a primal difficulty.

Unbridled objectification may soon turn to alienation. The underlying misconceptions unwittingly arise from 'category

errors' that are very powerful, yet rarely distinguished or discussed. Such discernment requires unfamiliar thought

about our working axioms. For this reason our first folly receives the lengthiest deliberation. The later appendix

offers a tabulated summary and illustrative graphs.

1. Medical diagnoses and treatment models are the most effective for dealing with human ailments. These methods are clear, authoritative and evidence-based. They should be precedent

wherever possible.

This is mostly and uncontentiously true when dealing with ‘structural’ diseases of the body, particularly where

the condition is localised and acute. Common examples: hip fracture, pneumonia, appendicitis. With any of these

we are grateful and satisfied with competent and courteous biomechanical attention. With other kinds of health

problems this effectiveness becomes much less clear. The ‘medical model’ then loses its unrivalled command and

precision; for example, when dealing with complaints that are not structural, but experiential, ‘functional’ and

stress-related. What are these? They include an ocean of ill-defined but physically distressing complaints which

present to GPs and various healers; they become loosely packaged with labels such as migraines, dyspepsia, dysmenorrhoea,

tension headaches, IBS, PMS and ME. Then there is the vast range of human anguish – the psychiatrically classified

Mental Disorders: disturbances of behaviour, appetite, mood or impulse (BAMI).

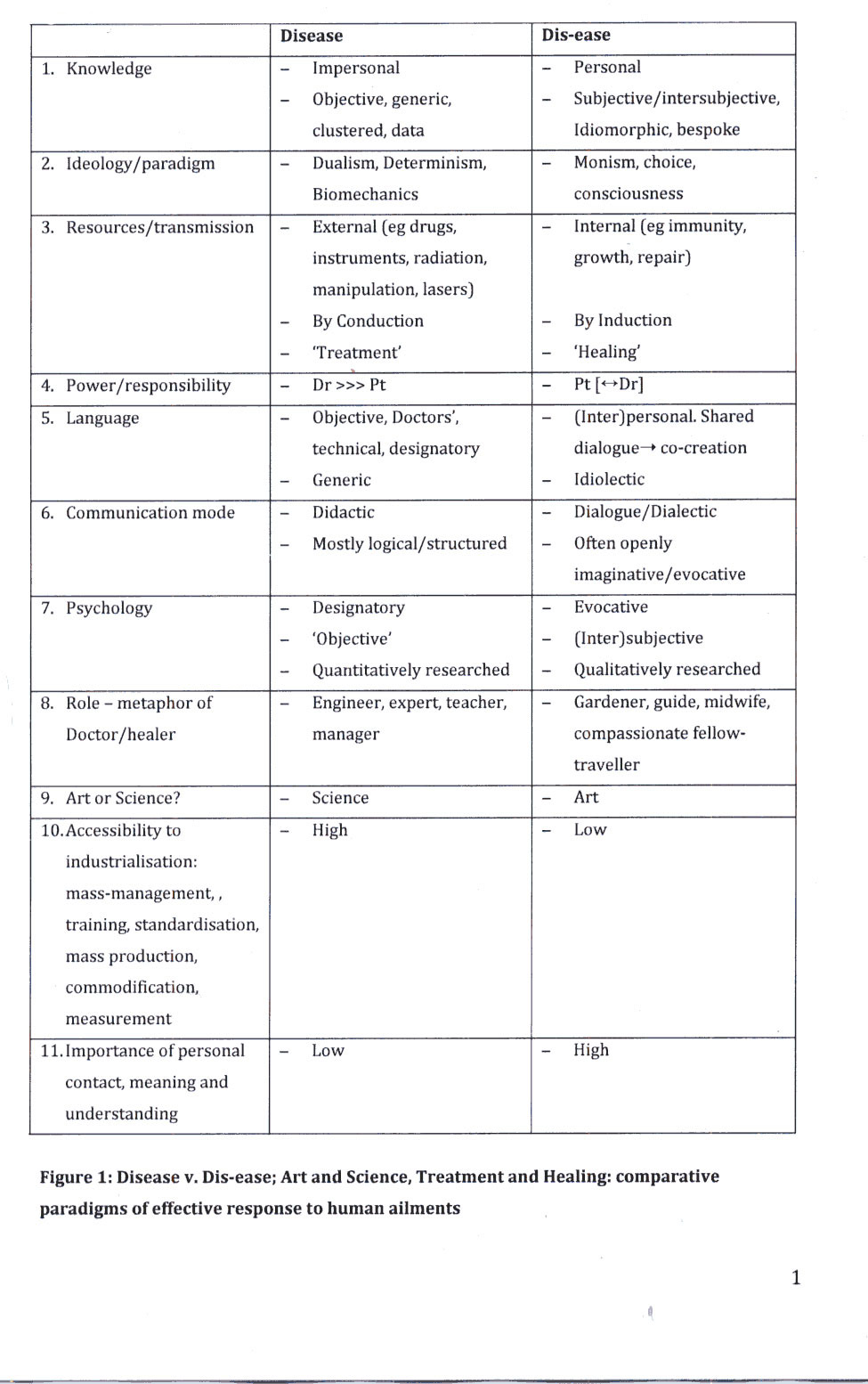

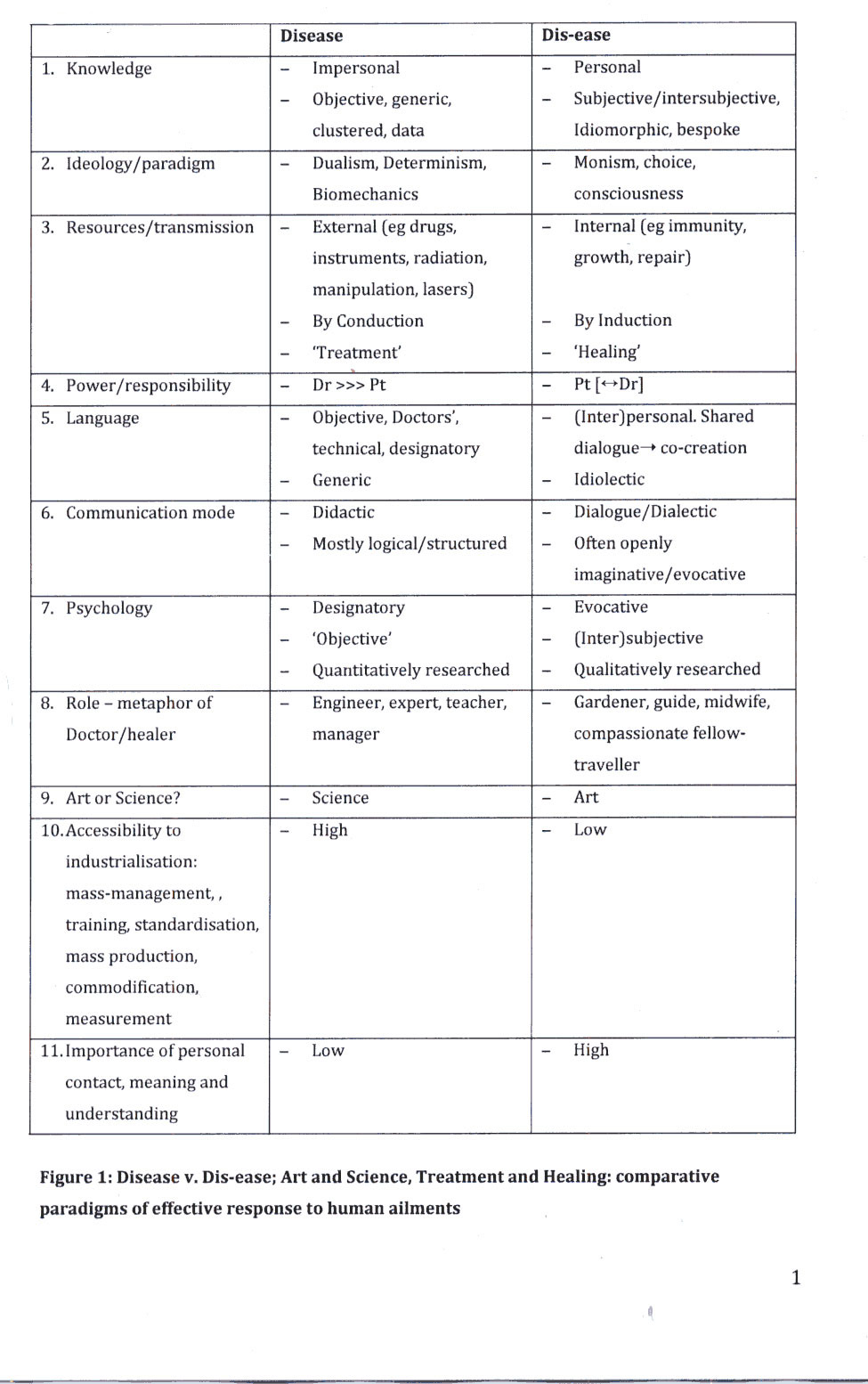

There is a useful general equation that can guide our designation and understanding:

structural change = disease; functional disorder = dis-ease.

Although the words look very similar, our optimal methods for approaching

and apprehending them often need to be very different. For example: structural disease can be tightly clustered

into generic diagnoses where individual variation and meaning

are relatively unimportant. ‘One size fits all.’ In contrast, functional dis-ease is more likely to be idiomorphic: the generic pattern now less decisive, but the individual meaning

and variation crucial. ‘Only the wearer knows where the shoe pinches.’ As we will see, erroneous conflation of

the two leads to many other follies in practice, from individual consultations to national healthcare planning.

Such conflation is easily done, and then often very hard to undo. Because of its importance, this subtle but powerful

distinction is worth paying time and attention to understand.

The dazzling success of biomedical science in tackling many structural

diseases may blind our perception of its competent boundaries. Dazzled, we fail to see that overuse of medical

diagnosis and treatment in areas of dis-ease becomes counter-productive. This kind of misplacement is complexly

inefficient: it frequently leads to eclipse or displacement of more personal and fruitful types of dialogue and

understanding – the keys to healing, growth and resolution. Without these, compassion perishes.

There are problems, too, about the integrity, the ‘realness’, of

our research and knowledge when we confuse or conflate these two territories, of disease and dis-ease. Current

currencies of quantification and ‘evidence-basis’ are now a shibboleth to any ‘service provision’. Despite this

assigned pre-eminence, such esteemed quantitative research becomes less valid when applied away from the shoreline

of solid-state pathology: disease. Problems arise when investigating dis-ease because this is primarily a form

of communicated experience, not a stable or simple physical state. Yet, no inner experience can be measured directly.

We can only access and measure external, associated behaviours or verbal reports. This is hard for those healthcare

workers in thrall to objective scientific method: they hope and believe that their measurements or observations

reliably indicate private experience. But such formulated indices are, alas, never equations. Research of internal

experience here becomes inescapably ‘contaminated’ by a myriad of personal, relational or institutional factors.

For example, attempts to measure ‘mood’ or ‘well-being’ are fraught with subjective and interpersonal intrusions

and distortions and can never match the clarity or precision of, say, blood electrolytes. To compound the problem,

the contaminating factors (eg of conscious or unconscious suggestion, influence or wish) are themselves unmeasurable.

In this welter of uncertainties, away from bodily structural disease, science can only operate with severely annotated

compromises: ‘pscience’. Organisationally and economically, this introduces myriad tangles to the meaning and integrity

of statistics. Projects such as ‘Commissioning’ and ‘Payment by Results’ then entice specious clarity, with all

its inevitable difficulties and corruptions.

All cultures are defined by a prevailing rhetoric. In our industrialised

healthcare the categorised and the quantified are now hegemonic. Flawed pscience is now precedent to an unquantified

vernacular, however apposite. Such statiticised pscience thus proceeds with a kind of abstracted, regal authority

in areas of delicate interpersonal uncertainty. This is a growing problem, most clearly in psychiatry and primary

care: here the insidious change has become cultural, and has, by definition, led to a diminution of professional

awareness, analysis and debate. The interpersonal skills deriving from these perish, too.

Such areas of healthcare need to reclaim those receding and very

different kinds of imaginative intelligence. For example, pscience is likely to assess a distressed person by administering

a quantifiable mood questionnaire. A more holistic psychology asks: ‘What is it like to be this other person; to

have lived their life? What is the meaning and significance, for them, of this distress? What is the meaning and

significance, for them, of me, now? What needs do I need to address that they might not (yet) be able to articulate?

Answers are hardly to be found in academically studied or managerially designated psychologies. Only a personally

imaginative and engaged sentience can lead us to bespoke compassion.

Isn’t all this just overcomplicated and academic? No.

Why, then, is it important? Because our conventionally assumed or

conferred language and knowledge largely configure our pattern of understanding and engagement with others. How

we think, speak and document will determine what we do. If our language eschews personal resonance and understanding,

our actions will follow suit. Any System, in excess, will offer specious clarity and certainty. We must be vigilant;

an overreaching scientism will become a pyrrhic progress. Overusing the language, understanding and interventions

of disease in the territory of dis-ease is such a seductive but debilitating error. Like a mislocated expedition,

it leads to a massive misapplication of effort and resources. Not only does this lose us efficiency and economy.

The loss of personal understanding is even more serious: unnecessary attribution of illness mentality and behaviour

can be profoundly disempowering. Myopic and inapt labelling generates its own disabilities. The loss of personal

language, autonomy, agency and responsibility – these are all causes and casualties of an over-reaching medical

model. In our preoccupation to measure we often deskill and desensitise ourselves in the unmeasurable. A mind full

of generic dicta, data and algorithms cannot heed the individual voice.

Such losses can largely account for the recurrently exposed, shocking

and grotesque examples of basic failures of care in hospitals – institutions which are heavily invested with high-technology

and managed care-pathways.

We are faced with a serious and perennial conundrum: in our muscular

but blind resolve to treat, we may easily destroy the gentler sentience to heal and humanely care. Compassion may

be powerful in effect, but it is fragile in viability: it needs a mindful and respectful space and ambience to

survive.

2. Healthcare is important and complicated. All practitioners should be tightly monitored and controlled.

Increasing healthcare management is bound to be to the patient’s benefit.

Yes, but only sometimes. The caveats for this are broadly similar to the section above. For example, the rules

and regulations addressing safety in a Cardiac Surgery Unit should be strictly enforced. Exceptions would be very

exceptional, if ever. In contrast, such tight governance is much less helpful when attempting to relieve functional

complaints. For example, a perfectionistic lonely person with tension headaches, or another incapacitated by rage

and grief at the discovery of a major infidelity, or another enervated by mysterious polysymptoms since his wife

became pregnant. In these functional disorders, the therapeutic effect of the practitioner depends upon imaginative

skills of personal contact and suggestion. Institutional or formulaic management are likely to run counter to these:

rigid management eviscerates compassionate imagination.

There are parallels here to family-life and how we bring up children.

The balance we choose between rules v freedom and structure

v spontaneity, etc, will vary with the child, its age, the situation,

and so forth. Families where structure and discipline are rigid and excessive will yield children who may appear

orderly and well behaved, but are stunted in their capacities for creativity, initiative, expression, joy and intimacy.

Necessary conflict, too, will be turned inwards or displaced, with all the destructive effects within and without.

Organisations that are over-managed show equivalent afflictions. Such

harassed groups suffer from defensive proceduralism, low-morale, high sickness rates, scapegoating, and a fascinatingly

subtle range of subversion, both conscious and unconscious. Paradoxically, such depletions are retroflected casualties;

the result of management compulsively ‘driving’ efficiency. Over-controlling parents rarely get what they intend.

Compassion, too, requires our intelligent flexibility.

3. Mass-production and standardization

must be a good thing, if it makes things more available.

We don’t question this with washing-machines or ball-bearings. Entering the arena of

healthcare, we can still extend this confidence to, say, pharmaceuticals, surgical materials and certain procedural

treatments, eg cataract extraction. This remains true so long as individual variation, subjective complexity and

personal understanding are relatively uninfluential. In contrast, chronic and functional complaints confront us

with the importance of individuals’ variation of experience and meaning. These all-too-human factors elude quantitative,

formulaic and procedural approaches. We must here develop more flexible, ‘crafted’ and individually addressed responses.

Centrally-programmed factory workers are not equipped for this.

What are these elusive variables, and how are they important?

Much of this we know from everyday experience. For example, most of us, when distressed by personal or relationship

problems, find difficulty in describing, expressing or explaining these. We are likely to have all kinds of fears

about sharing or disclosure. How a listener or helper might respond becomes decisive as to whether and how we do

this. In this process we are exquisitely sensitive to the subtlest interpersonal signals and changes. Example:

how we feel with apparently tiny variations of voice, timing or body language with a verbal greeting or a handshake.

For all their power, such nuances of interpersonal influence are almost impossible to measure or manage directly.

Paradoxically, though, over-management may stifle, even extinguish, an emotionally-literate environment, which

creatively respects the fragile complexity and uniqueness of each interchange. Compassion needs space and oxygen

to flourish. Analogies with parenting are, again, clear and prophetic.

4. Competition, commissioning and commercial

pressures will raise standards of care.

In industry, encouragement of these ‘3Cs’ makes much sense: in providing technical services and physical commodities,

and the manufacture and sale of objects. With complex welfare activities it, again, leads to a similar pattern

of the unintended. The ‘3Cs’ solution often becomes more problematic than the problem it is attempting to address.

For example, if we attempt to commodify, and then trade, in ‘packages of care’, how do we pre-scribe the changing,

often inexplicit, complexity of people’s needs? And then any need for flexibility and sensitivity of response?

How do we then standardise a package and a price? If we mandate such specification, what is the human cost of doing

so?

To illustrate such problems:

Mr C is 62 years and needs a total hip replacement due to premature

osteoarthritis. He is otherwise very fit, healthy, happy and actively involved in his work and large family.

Mrs D is 83 years and also needs this operation. She is a childless

widow: she had a stillbirth 60 years ago and never again conceived. Her beloved husband died of cancer a year ago.

She now lives alone; lonely, with stoic and brave melancholy. She was an only child and was sexually abused: she

is wary of any kind of physical care or examination. Her complex diabetes and emphysema add to her vulnerability,

but she tends to deny this due to her aversion to any kind of dependency.

Clearly, Mrs D’s anaesthesia, surgery, physical recovery and psychological

resilience are all more likely to be problematic than Mr C’s. All these processes will require intelligent and

imaginative care. How can such delicate compassion be predictively and commercially contained, controlled or costed?

How do we have ‘diagnoses’ for such kaleidoscopic but decisive human complexity? How will each separate Specialty

or Trust precisely delineate and invoice its responsibilities?

What happens with a system of competitive commissioning? Practitioners become controlled by their thraldom to Trusts,

and the Trusts are in thrall to optimising their profits and ‘performance data’. Thus are they likely to fulfil

to the letter (only) their contractual obligations. Officious practice flourishes; managers, even lawyers, direct

and tailor individual practice to suit institutional and commercially negotiated ‘contracts’, and thus policies.

These replace more humanistic or holistic practice: encounters guided by broader and longer-term views, and informed

by a growing understanding of each particular individual.

Under such a system, over time, we lose vocational practitioners: those motivated primarily by the pursuit of humane

enquiry and healing relationships. These become replaced by ‘Teams’ of management-directed, piece-work biomechanics.

Chosen vocations become managed careers. Thinking and activity turn institutional, not interpersonal. Resources

become increasingly commandeered for defensive and offensive organisational fights and feints: meetings about meetings

– negotiation, litigation, imposing but slyly tendentious statistics, PR, ‘spin’… Services that for several decades

existed in a state of trusting and cooperative confederation, now become mistrustful competitors: Trusts (!). The

patient is now a commercial proposition: if he generates revenue (for the Trust), then find reasons to provide

a service; if he does not generate revenue, then find reasons swiftly to discharge him somewhere (anywhere) else.

‘It’s not our responsibility.’

Amidst this Darwinian struggle for survival, can our compassion really

be commissioned or commodified?

5. Specialisation

is always a good thing. It provides greater expertise when and where it is needed.

Yet again this is most impressively true with well-defined structural disease, but often counter-productive when

dealing with more complex and less stable situations. Positive examples of the use of specialisation are clear

and obvious. If we have a knee problem that requires surgery, then we want, not just an orthopaedic surgeon, but

one who specialises in knees. The idea is that we can divide the body up into smaller and smaller parts and systems,

and thus concentrate knowledge, effort and expertise with greater precision and efficiency. This is viable so long

as we are dealing with disease that is stable and confined to a body-part or system. We can term this fragmenting

specialisation ‘Anatoatomisation’.

This kind of specialisation can become far from helpful when applied away from the stable, localised disease scenario.

To illustrate:

Mr S is age 70 years. Two years ago he developed an aggressive form of Parkinson’s Dementia,

shortly after his retirement. He had been an extremely educated, fit, diligent and disciplined man, holding a senior

post in international diplomacy. His multidimensional decline has been relentless and tragic. He has become an

insentient and incontinent shell of his former self, recognising no one and requiring constant care. Amidst this,

his beleaguered, self-sacrificing wife discovers a breast-lump, a cancer. She then has chemoradiotherapy, which

itself makes her ill, in the hope of a cure. As Mrs S struggles to recover, Mr S’s decline is unabated. He has

unmanageable ‘episodes’: he freezes, falls, develops chest infections, deepening deliria. Each of these needs his

admission to hospital, and each time it is to a different Ward and a different ‘Team’, who do not recognise him.

Each team then routinely refers him on to further specialist teams: to Gerontology (for his age!), to Neurology

(for Parkinson’s), to Elderly Psychiatry (for Dementia), to Urology (for recurrent urine infections), to Respiratory

Medicine (for chest infections). None of these teams seems to acknowledge the larger picture, and what is needed

in terms of wise, humane contact; continuity, containment support and comfort. Mrs S is an intelligent woman, but

now fatigued, despondent and confused by the constantly changing medical personnel, designations and venues.

‘Why does he need yet another brain scan?’, she wearily asks a bustling and brisk Neurology Registrar.

‘Just to make sure we’re not missing anything’, comes his clipped reply, his tone of defensive authority primed

by Trust Protocol.

Thirty years ago this unneeded and very expensive brain scan would not have been available. Nor would the panoply

of specialist teams. Mr and Mrs S would have had something else: continuity of care by a known general physician

on a particular ward. This broadly-based clinician and dedicated nursing staff would have provided the personal

investment, familiarity, acknowledgement and understanding that were needed to nurse and palliate all of these

‘episodes’. They would have seamlessly apprehended the human needs, not just of the ravaged Mr S, but also his

exhausted wife. They would probably not have used the word ‘compassion’, but it would have been woven into their

experiences, acts and utterances. Such traditional skills are easily displaced by the often specious imperative

to ‘specialisation’. The whole is more than the sum of its parts: compassion is a tender and fragile fruit of holism.

Ms T is a 38-year-old single woman with a

son of four years. Her persona of engaging warmth and polite cooperation belies her deeply troubled and troubling

history. A product and victim of, and hostage to, a painfully unhappy parental marriage, she has spent most of

her life trying impotently to break free, to establish an autonomous and wholesome self. But she has not the self-esteem,

the internal model, or sense of entitlement to do any of these things. She is like a blinded, enraged, captive

creature convulsively throwing itself against the bars of its cage, trying to find the outside. The symptoms signalling

this impacted struggle have been wide-ranging. They have been shepherded and clustered by a parade of specialists

over many years: mood disturbance and instability, gastritis, eating disorders, intermittent alcoholism, impulsivity,

irritable bowel syndrome, obsessive compulsive disorder, migraines, menstrual dysfunction, eczema…

Each specialist attempted to subsume, quell, or at least contain, her disturbance with their own language and circumscribed

focus of the medical model. Sometimes, paradoxically, such specialisation led to her being the object of exclusion

instead: once she was lost between the GP Counsellor, the Psychiatric and the Alcohol Services, who each said that

one of the others should be responsible. Despite seeking helpful engagement, she was extruded by all three: ‘she

does not meet our intake criteria’; ‘It’s not our responsibility…’

Dr W, her General Practitioner, has learned over many years that such marathon, polymorphous disturbance is usually

signalling some failure of personal evolution, some frustration of gratified belonging. It lies behind and beyond

any specialisms, their language or measurements. He remembers an old mentor saying of his endeavours to help such

people: ‘You need patience with patients, and patients with patience’. But Dr W knows now that it requires also

evocative but structured encouragement, to safely uncover and decipher what lies beneath. He arranges an hour’s

appointment with Ms T, to try to take them both from a world of fragmented and serial specialisms, to a holistic

perspective deriving from, and imbued with, personal meaning.

The polyclinic Practice Manager is alerted, and now uneasy: ‘We have pressure on clinic rooms, doctor, and this

kind of work takes up a lot of time, and earns no additional “points” for the Practice … in any case, all the other

doctors have said this kind of work is not your responsibility …’

*****************

Is there a more crystalline coda for these Five

Follies?

And the question arising? In a healthcare system

increasingly determined by the quantifiable, the commercial and the industrial, how do we restore, and then assure,

the primacy of holistic, human care – the quality and continuity of our personal contact with others? In our busy

and difficult jobs, every day and in every consultation, how do we create afresh, then nurture, an ever-evanescent culture of compassion?

*****************

‘Is it progress if a cannibal eats with a knife

and fork?’

Stanislaw

Lec, Unkempt Thoughts, 1962

*****************

APPENDIX

Please click

here for Fig 2 and Fig 3

A slightly shorter version of this article was submitted to the Secretary

of State for Health earlier this year. It was subsequently published in the Journal

of Holistic Healthcare Vol 8. Issue. Dec 2011.

Interested?

Many articles exploring similar themes are available via David Zigmond’s home page on www.marco-learningsystems.com

David Zigmond would be pleased to receive your

FEEDBACK

Version: 2nd May 2012

|