|

Transactional Analysis in Medical Practice: David Zigmond

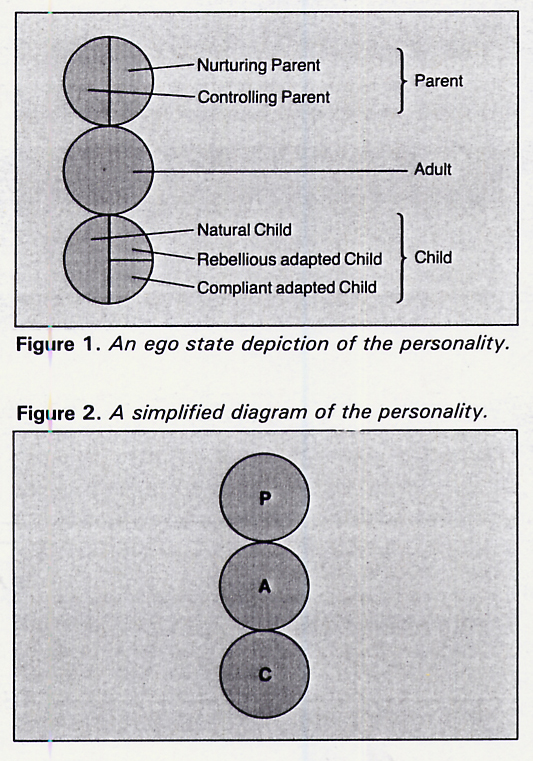

Transactional analysis (TA) is an extensive theory of mental and behavioural functioning with particular reference to its developmental and social aspects. This article makes no attempt to be a comprehensive survey of TA. Instead, attention is confined to areas in both medicine and TA where a combination of these skills offers clear insights and rapid effects. I have not made any attempt to describe the role of TA in psychotherapy, which is a large and complex subject. Transactional analysis has its foundations in the work of Eric Berne, who formulated its basic tenets from the late 1950s until his death in 1970. Berne was a medically trained psychoanalyst who felt increasingly constrained and dissatisfied with traditional psychoanalytic theory and technique. He was critical of several features of psychoanalysis as a method of treatment, but this is not relevant to the present discussion. He also felt that psychoanalytic theories tended to formulate predominantly in terms of pathology within the individual, thus minimizing the framework of social relationships within which the individual necessarily functions. This theoretical bias of psychoanalysis derives from the medical model, and Freud's original training as a neurologist is important in the foundations of this outlook. Berne intended TA to deal with the interactional aspects of problems in a way that was demonstrable and relatively unambiguous. He felt that the language and concepts of psychoanalysis had become obscure to those it was designed to help, and that it was liable to engender mystification, passivity and dependence, rather than the reverse. He therefore constructed an easily understood system that formulated problems in terms of difficulties between persons. The social matrix encompassed by TA ranges from a relationship between two persons, to one between the largest social groups. Pattern of Interest for TA This interactional emphasis of TA is reflected in the pattern of attention it is receiving in the UK today. For example, more interest has been shown in TA by general practitioners and others working outside institutions than by hospital doctors and other institutional workers. Hospitals are designed to deal with problems of individual pathology, and this is perpetuated by the referral of designated patients who are referred to hospital as 'the problem'. Even psychiatric patients are liable to be investigated, processed, labelled and despatched in much the same way as people suffering from organic complaints. The general practitioner has less refuge behind the protocol, paramedical staff and complex routines that protect the hospital doctor and contain the patient. He is more exposed to patients and their families 'in vivo' and he must forge for himself methods of living and working with them that sustain his own health as well as theirs. I discussed in an earlier article (Zigmond 1977a) how the emotional problems of those who help are often quite as important as those who seek their assistance. For a broader and more effective view of our consultation problems, it is therefore an advantage to be familiar with a model that formulates the problem bilaterally; that is, between patient and doctor. The traditional Medical Model, which confines its interest solely to the patient, has evident practical shortcomings in this respect. It may lead also to complex ethical and epistemological problems, particularly in psychiatry (Szasz 1961). Awareness of our personal investment in treatment is a necessary counter to these dangers. TA, too, has much to offer in dealing with these difficulties. It is very relevant and edifying to the 'here and now'. Furthermore, its terms and concepts have a precision and clarity often lacking in psychological theory; this reflects Berne's interest in the educational aspects of psychology and psychotherapy. Ego States An ego state is a discrete system of thinking, feeling, behaving and communicating. We all have three ego states, and usually most of our energy is invested and evident in only one of these at any one time. Ego states are colloquially called Parent, Adult, and Child. (When these words are capitalized they refer to ego states, not people.) The Parent Ego State The Parent ego state is the complex of imitative patterns that we learn from parents and other parent-figures when we are children. The latter include older siblings, school and such insidious influences as television and advertisements. As children we perceive them all as how grown-ups are, or should be. The Parent thus introjects not only actual parents but cultural values and slogans also. Real parents have both controlling and nurturing functions. Without parental control, our early life would be prone to many avoidable and gross hazards. Emotional and physical nurturing from parents is evidently necessary for optimum and pleasurable survival and growth. In the Parent these experiences are incorporated as the Nurturing Parent, and the Controlling Parent. When our energy is resident in our Nurturing Parent, our feeling and behaviour will be that of acceptance, care and concern. Our voice and gestures will be protective and soothing. When functioning in our Controlling Parent, our gestures and voice become commanding, firm and harsh. At these times we know what is right (even when we are mistaken). Parent ego state functioning is accompanied by postures and feelings of being 'one-up'. The Adult Ego State The Adult is the reality-tester and probability-estimator in the personality. It is the part of us that is objectively observational and logical, operating much like a computer. The other two ego states tend to be experiential, reactive or demanding, whereas the Adult functions by collecting, ordering and storing data and figuring things out. This applies equally to such diverse problems as calculating a grocery bill and to analysing and taking decisions about a complex emotional problem. It can be seen therefore, that the Adult is essential to continence and survival both in our intrapsychic and social functioning. When we are in our Adult ego state our feelings, thoughts and demeanour will be experienced as considered, stable and impartial. The Child Ego State The Child ego state is the world of experience and reaction-patterns that we carry within us from the time of our actual childhood. Children's behaviour is either natural, or influenced in some way by more powerful grown-ups. This leads to two aspects of the Child, which are called the Natural Child and the Adapted Child. The Natural Child is spontaneous, self-centred, and vivid both in its experience, and the way it is experienced by others. It is the part of us that is curious, creative, impulsive, expressive, demanding, and unashamed. It is the part of us that can laugh or cry without social debt of embarrassment. The Adapted Child has learned to adapt to the demands of more powerful and controlling grown-ups by strategies of either compliance or rebellion. Essentially the Adapted Child conceives and feels itself to be 'one-down' and potentially or actually controlled by others. As small children we often felt powerless and at the mercy of others whom we perceived as being imbued with magic powers. Sometimes as a strategy of redress or retaliation we would fantasize that it was the other way around, so that we became omnipotently powerful. These feelings of paranoid impotence or grandiose influence are present in all of us to varying degrees. How we come to terms with these primitive parts of ourselves determines in broad outline the pattern of our mental and social functioning. Also, there is a powerful connection between psychological and physical pathology and the content and control of the Child, which I explored in a previous article (Zigmond 1977b). Diagrammatically, we can illustrate the personality as shown in Figure 1. In Figure 2 the diagram is presented more simply.

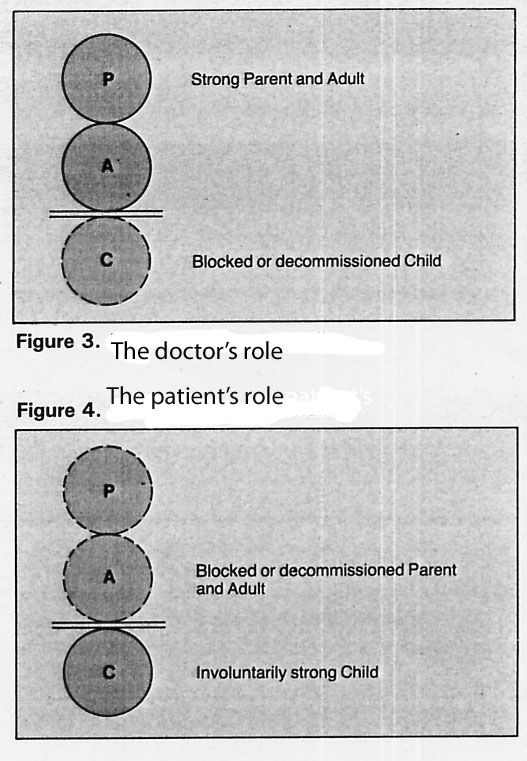

Doctors' tasks involve mainly controlling, nurturing, and problem-solving skills. We are expected to show compassion in the face of suffering, and to be able to counter a wide variety of dangers with parental strength and know-how. Our work also involves a great area of objective observation, together with collection and collation of data and subsequent decision-making. In short, we function largely with our Parent and Adult. Interference by our Child is usually thought of as, at best, distracting or, at worst, disruptive and dangerous. As we shall see, this role is cast partly by the nature of the therapeutic situation, and patients' idealized expectation of doctors. Often, however, we have a more personal reason for denying our Child expression and recognition. This usually derives from our own need to be strong and inviolable, as a defence against being the reverse, i.e. helpless and at the mercy of others. Consequently, we may thrive on looking after seriously sick or compromised people, and consider ourselves expert in knowing what is 'good for' others. However, we do so at the risk of becoming out of touch with our Child. The world of chaos, strong feelings, spontaneity and vulnerability is kept strongly in check, if not denied by our Parent and Adult ego systems (Zigmond 1977a). A working diagram of many doctors can be represented as shown in Figure 3.

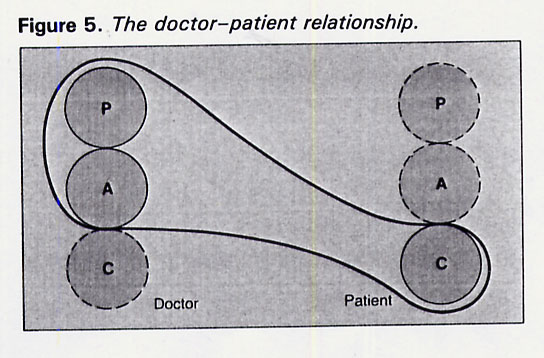

Illness is often experienced as a mysterious and alien intrusion, which poses a grave threat to our physical and psychic power and integrity (Szasz 1961; Zigmond 1977a). In this way it equates with the Child's primitive fear of powerlessness and erosion of autonomy. Those who are ill, or believe themselves to be ill, thus tend to function from the Child part of themselves and see their medical attendants as parental figures with magical powers. Sometimes this view is fascinatingly near the truth. A diabetic man who is roused from a hypoglycaemic coma by an injection of glucose could not possibly manage this for himself. A non-informed observer could, understandably, view the doctor's intervention as magic. Both the patient and the observer in this situation function in a passive and dependent Child position. Their Parent and Adult are either non-functioning or powerless to intervene. This can be shown as in Figure 4. Such a necessary and clear-cut pattern is not always operative, however. Often the patient is forced into a Child pattern of response because of the inflexibly Parental nature of his doctor who demands complementary acquiescence in those he is dealing with. In this situation the patient may show either compliant or rebellious Child responses, depending on how he resolved (or failed to resolve) conflicts with his own parents. Also, there are those people who habitually react from their Child, hoping to 'hook' either the nurturing or critical parental responses from others. Such people have inadequately functioning Parents and Adults of their own and look to others for directives and protection, thus maintaining a regressed position in which they abdicate responsibility for their actions and feelings. Due to the reservoir of unfinished business with actual parents, the Child is constantly looking for certain pay-offs, which are collected from the Parent ego state in others. Such pay-offs range from hostility and punishment to protection and expiation of guilt. Psychodynamically, the replay of these archaic dramas may be thought of as ineffective attempts to resolve the unfinished conflict. These strategies are played out, in varying degree, by the Child in us all and make up the nucleus of what in Transactional Analysis are termed 'Games', which will be surveyed in Part 2 of this article. The important principle is that each person carries with him into the consultation unfinished business with parents. Ensuing dialogues are, therefore, often more relevant to the Child's archaic experiences, than to the business immediately at hand. Symbiosis Symbiosis is a state of mutual dependence where one individual provides certain things that the other does not have but needs. As I have already indicated, doctors tend to function in Parent and Adult ego states, and patients, at least within the medical consultation, are often functioning in their Child ego states (Figure 5).

Such symbiosis may have fruitful or fruitless outcomes. Let us take an example of each. Case 1. Benign Symbiosis; Helping the Needy Mr A. has just suffered a heart attack, has a great deal of pain, is breathless and also frightened and bewildered as to what is happening to him. He is clearly helpless and functioning in his Child ego state. On his arrival at hospital a nurse, 20 years his junior, holds his hand, strokes his face and says gently "Don't you worry dear. You've had a heart attack but everything's going to be all right. The Doctor's going to give you an injection to take away the pain and then you'll feel fine". This nurse is clearly functioning in her Nurturing Parent ego state, much to Mr A.'s gratification. If she were to give him Adult data concerning the mortality of myocardial infarcts, or a Controlling Parental rebuke for making a fuss, the outcome would be far less satisfactory. Case 2. Malignant Symbiosis; Needing the Helpless Stephen, aged 11 years, collapsed without warning in the playground. He was limp and unconscious on his admission to hospital. A sample of his cerebrospinal fluid indicated a Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Angiography showed an inoperable arteriovenous malformation. He was unconscious for a day, aphasic for a week and it was several weeks until his hemiparesis reached near total recovery. For this reason he stayed on the ward long after his dramatic collapse. Sister B. was a rigid, efficient, authoritarian woman in her late fifties who ran the ward with stark efficiency. She was a woman whose gratification was derived almost entirely from her work. Her life outside the hospital was barren and lonely. She was excellent at dealing with sick children, but alienated and hostile to healthy, autonomous people; she was emotionally dependent on those who were physically dependent on her. Although Stephen's recovery was definite, it was slow. He became despondent about his illness, and the length of his stay in hospital. The following dialogue ensued between Sister B. and Dr C., the Paediatrician:

It was evident that Sister B. was capable of relating to Stephen only when he was ill, and this represented her own need to control those who were dependent on her. She felt lost and threatened without this role of Parental dominance. On her retirement from nursing she became extremely depressed.

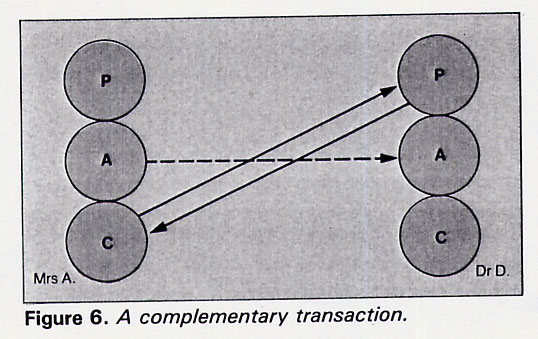

Hazards of Rigid Symbiosis This case illustrates some of the hazards of rigid symbiosis. It is very different from the previous example in both intention and outcome. Such interlocked symbiotic relationships are as common in the helping agencies as they are in marriages and families; the consequent confusion and frustration also follow similar patterns. Symbiosis has its roots in a type of compensation. When we deny powerful needs and impulses in ourselves, we will either be intolerant or solicitous of these attributes in others. If it is the latter, then there is a high chance we will work in one of the caring professions. In effect, we seek out and look after the part in other people that we disown or suppress in ourselves. Our needs may then be fulfilled vicariously through a state of mutual dependence. The helper's part in such a tacit contract reads: "I will be strong if you will be weak. I will support, protect and guide you so long as you are helpless, obeisant and obedient. I will not express my feelings so you must have and enact them for me". Reciprocally the patient’s role in the collusion reads: "If you will be my grown-up then I will make you feel clever, potent and important. To make sure that's so I will be passive, aimless and dependent". Such dependence upon our patients or clients for our sense of power and vicarious expression of locked-up feeling is often not conscious. In the short term this may be harmless. The long-term effects, however, may be similar to many other relationships which can thrive only on a radically unequal power distribution. Because gratification of both partners depends on a rigid status quo where no growth is possible, a sense of entrapment, waste and resentment is likely to evolve. This may account for many harried and depressed doctors who are uncomprehendingly dependent on their patient's dependence. Such familiar treadmills are thus internally motivated, not externally necessitated. Some of the consequences of these compulsive styles of behaviour were explored in an earlier article (Zigmond 1977b). Concord and Discord Often when communications break down it is because different ego states are responding to one another in such a way as to make meaningful dialogue impossible. If a transaction is 'complementary' then the ego state of one person is recognized and answered by the complementary ego state of the responding person. Such a transaction is concordant, and may continue indefinitely. Often, however, a transaction is 'crossed', and then the ego state of the responding person is not complementary to the ego state of the person who initiated the transaction. Communication will then either reach an impasse, or exhibit evident discord. Both partners in such an interchange are likely to be left feeling bewildered, angry or hurt. Case 3 As an example, let us say that Mr A.'s wife hurries to the hospital and sees the attending doctor, Dr D. She is frightened and bewildered by the collapsed and drugged state of her husband, and overwhelmed by the technology that surrounds him. She is fearful, alone and evidently functioning in her Child ego state. Tremulous and clutching her handkerchief she turns and says to Dr D. "Is he going to be all right, doctor?". Dr D. notes that this question comes from her Child, not her Adult ego state. He decides this is not the time for a technical (Adult) dialogue. He responds from his Nurturing Parent, saying "He's still very ill but I think he's a lot better. We can never say for sure, but I think he's going to be all right. We'll certainly explain anything to you that you don't understand. I can see you're very upset at the moment. Would you like to sit here a while and have a cup of tea before you leave him tonight?". This interchange can be expressed as shown in Figure 6.

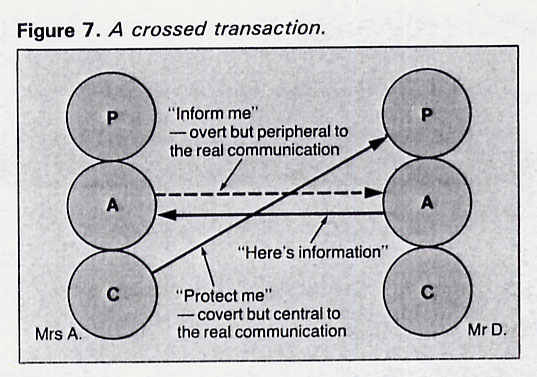

The important point is that the doctor recognized which ego state she was in. Her question "Is he going to be all right?" was ostensibly an Adult activity searching for data, but really the Adult pose was conventional bravado (hence the dotted line). The core of her communication came from her Child, as demonstrated by her faltering voice, her tremulousness and the tenacious grip of her handkerchief as something familiar and stable she could hold onto at a time when all else seemed to be receding into the unknown. Her question was more a plea for care and protection than a quest for knowledge. Both parties in this encounter probably left it feeling richer and better. Case 4 Let us now look at an (exaggerated) alternative. Dr D. does not tune in to her present dilemma and needs; he answers merely the verbal, 'official', component of her communication and remains oblivious to her intonation and body language. Consequently he replies, "Well, his myocardial infarction is complicated. His ECG and chest x-ray both show a large left ventricle and he's probably had severe hypertension for some time, which should have been treated. His left ventricular failure has improved with the intravenous frusemide but he's still throwing off a lot of ventricular extrasystolic beats, which shows a poor prognosis. Recent papers have indicated something like a fifty per cent mortality in such complicated cases". This interchange can be represented as in Figure 7.

The outcome, of course, is likely to be unsatisfactory. Mrs A. now feeling even more frightened, alienated and helpless in her Child ego state. She perceives the ubiquitous technology as oppressive and inscrutable. The doctor has become a Parental monster because he seems to have so much knowledge and power, but will not heed her relatively simple but vital needs. She bursts into tears, which the confused Dr D. now tries to stem with his Controlling Parent. "There, there, dear", he says, "you don't want your husband to see those tears do you? I'm sure he won't want you to be upset like this". In reality it is Dr D., not Mrs A., who is threatened and bewildered by her tears. Mrs A. now cannot be comforted. She sobs internally, swallows her tears and flees her persecutor. As she goes she mutters some half-formed apologies and statements of self-reproach. Dr D. now retires to the Sister's office where, with tea and sympathy, he briefly slumps and despairs as to how difficult some people can be. Surveying the most recent ECG tracing he feels edified with the precision of his physical diagnosis. The transactional diagnosis was missed, however. It could have been equally clear and gratifying. References Szasz, T., The Myth of Mental Illness, Harper and Row, London, 1961. Zigmond, D., Hosp. Update, 1977a, 3, 325. Zigmond, D., Update, 1977b, 15, 903. Further Reading Berne, E., Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy, Grove Press, New York, 1961. The most systematic of Berne's writings on TA. It was his earliest book and is now an established classic. Berne, E., Games People Play, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1964. A brilliant and highly distilled book. This can only be fully digested after some other TA reading. Berne, E., What Do You Say After You Say Hello? Corgi, London, 1972. The most exciting and thought-provoking book from Berne was completed just before his death. It deals with the patterns of life plans we make in childhood. Harris, T., I'm OK—You're OK, Pan, London, 1967. This is the most readable and contagiously enthusiastic introduction to TA. However, it is now relatively outdated and evangelical in tone. James, M. and Jongeward, D., Born to Win, Addison Wesley, Massachusetts, 1971. A clear and fairly complete account of TA with lots of examples. Steiner, C., Scripts People Live, Grove Press, New York, 1974. Probably the most radical TA theorist since Berne. He focuses particularly on the contribution of social pressures in relationship difficulties and patterns of pathology. David Zigmond, MB, ChB, MRCGP, DPM, is a Psychotherapist at Hammersmith Hospital, London. The above article first appeared in the 15th December 1981/ UPDATE Interested? Many articles exploring similar themes are available via David Zigmond’s home page on www.marco-learningsystems.com David Zigmond would be pleased to receive your FEEDBACK

|