|

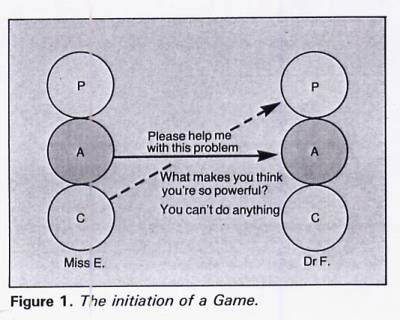

Transactional Analysis in Medical Practice: David Zigmond Many of the terms mentioned here were described in Part 1 of this article, which appeared in the 15 December 1981 issue of Update, page 1811. 'Strokes' Three decades ago a psychoanalyst named Renee Spitz1 made some radically important observations about children in institutional care. Those children who were reared in orphanages that offered little emotional recognition or caring for children, developed physical and behavioural disabilities with remarkably high frequency. This seemed to happen even when the physical environment, nutrition and sanitary arrangements were exemplary. The children continued to be notably behind in their growth and developmental milestones, and to be liable to intercurrent infections and its sequel in higher mortality rates. Remarkably, children seemed to survive much better in institutions where physical care and accommodation were appalling and the children were subject to much shouting, bullying and beating. The children fared better with negative emotional and physical contact than no emotional contact at all. 'Positive' and 'Negative' Strokes From such evidence, Berne inferred that we all need continuous signals from others, reifying our existence and demonstrating our significance. Berne called these interpersonal signals 'strokes'. At first, as infants, we tend to seek out and be satisfied with strokes that make us feel good in ourselves and with others. Feeding, stroking, caressing, playing and rocking are all part of the healthy and nutritious parent-child interaction. Such strokes are designated 'positive' and are the basis of psychic, social and probably much physical health, and have their counterpart in adult functioning. However, such is the essential need for strokes that if adequate positive strokes are not forthcoming, we will communicate with 'negative' strokes rather than have none at all. Negative strokes produce dissonant or hurtful feelings and experiences in the self and others. Transactional analysis (TA) maintains that some kind of stroking is as essential to survival and health as adequate nutrition or oxygen, and this is supported by repeated experimental evidence.2,3 At birth, and soon after, we wish only for positive and intimate strokes. However, the infant must take whatever strokes come her way because she is not free to move around or choose her parents or family situation. If mother is incapable of unconditional nurturing responses because of her own inhibitions, misery or harassment, it may be possible for the infant to obtain only punitive or controlling responses from her. At least when mother shouts or hits her she knows that mother recognizes her and she cares. Perhaps the little girl finds, when she is a little older, that mother strokes her when she is sick or miserable but not when she is robust and outgoing. So the way to get strokes from mother is to be suffering and helpless. It may be that mother feels lonely and empty and does not want her little girl to grow up; if the little girl is autonomous and healthy she will leave mother one day, so mother would rather keep her sick, dependent or passive. This is an example of `Malignant Symbiosis', which I outlined in Part 1. 'Malignant Symbiosis' in General Practice Such symbiotic patterns are frequent in medical practice, and echo similar patterns of pathologically dependent stroking within the family circle. For example, the little girl may grow into a woman who can only accept negative strokes by adopting a hurt and incapable role with others. She is likely to marry a man who keeps her in this role by either solicitude or bullying. Her medical history is likely to be packed with such painful, vague or intractable syndromes as migraine, dysmenorrhoea, miscellaneous abdominal pains, 'depression', 'anxiety neurosis', or agoraphobia. Her existential disability, however, can be formulated: "I can only be loved if I am suffering. The way to get strokes is to be miserable and helpless". It is important to realize that this strategy for living was constructed when the little girl was in no position to know better or to make a different arrangement with the parents, who controlled the strokes she received. Although anachronistic to her present situation and needs, it is perpetuated out of awareness. One of the basic principles determining our social behaviour and personal destiny is that we tend to seek out strokes of the same kind and in the same way as when we were small children and had little control over how others showed us recognition and care. It is notable also, that we not only provoke and collect responses from others that were the original source of our strokes, we also evoke the same archaic feelings within ourselves that were a by-product of these prototypal transactions. Case 1: Keeping People as Parents When Peter was a small boy his mother was often away from home due to frequent hospitalizations. His father had to work long hours and when he came home was often tired, withdrawn and depressed, offering Peter little in the way of recognition or nurturing. Peter found, however, that if he was clumsy, irritating or disobedient, his father would quickly be roused from his apathy to explosive anger. Only then would Peter know that father noticed him or cared for him in any sense. His father would often strike him and complain about his clumsiness, say what a nuisance he was and that he wished Peter had never been born. Peter's response was one of abject hurt and impotent bewilderment, but this was, perversely, a satisfactory exchange for father's demonstration of some emotional investment in Peter's life. Peter's unconscious system of stroking was: "To get noticed and cared for I have to be inept and naughty. My father will only show feelings for me if I end up being hurt". Peter is now 40 years old and his life is showing clear signs of trouble. Despite his evident talent and intelligence, he has always underachieved in his work. His marriage disintegrated because of his financial ineptitude and the ensuing domestic strain. During this time his wife would shout, "You're so useless! Can't you, just for once, do anything right? Oh, why did I ever marry you?...". The words his wife uses now and those his father used when Peter was three years old have an uncanny resemblance. The powerlessness, confusion and hurt he feels are the same too. He is recreating, with his wife, the original stroke protocol with his father. Even his doctor has noticed his accident- proneness, his forgetfulness and mismanagement of medication. The last time Peter consulted his doctor the latter became exasperated and angry because of his `wasted time and effort'. Curiously though, Peter seemed grateful and more settled with the doctor's anger than he was with his tolerance. The doctor felt bewildered and frustrated by his anger and Peter's apparently perverse behaviour. "After all," the doctor thought, "I'm only trying to help him". 'Scripts' In TA language, Peter keeps playing a game of 'Kick me' and 'Schlemiel', where he confirms how helpless he is, how aggressive others are and how hurtful life is. In his system of functioning, feelings of hurt are inextricably linked with being stroked. So long as he continues to function within this system he must go on being compromised in order to survive. This is the nucleus of Peter's 'Life Script'. A Script is the controlling and overall plan of a person's life. It is based on a set of decisions made early on in life, when the child is still powerless and unable to see his experiences in broader perspective. The child says to himself, "Well, this (i.e. indifference, bullying, anger, duplicity, discounting, etc.) is how life is. To get along with people I have to be thus (i.e. placatory, angry, insatiable, hurt, etc.)". Such archaic but decisive logic is incorporated into the Adapted Child ego state, where it administers the bulk of our automatic social responses. It dictates, through expectation and provocation, the kind of transactions and dramas a person will seek out or create throughout his life. The maintenance and facilitation of these early life decisions is the purpose of Games, which not only serve as a rich, though negative, source of strokes, but also conserve psychic and social homeostasis. The latter involves making, feeling and acting responses which are both predictable and repetitive. Such is the need for security through stability, that unhappiness, tissue damage or even death may be the currency offered in exchange for the sought-after strokes and interactional pay-offs. Games are thus subcomponents of the Script, which is so powerful and entrenched that it can often only be dissolved by decisive, insightful and often painful intervention. Some Scripts seem relentlessly tragic. Berne4 writes of these: "Tragic Scripts may be either noble or ignoble. The noble ones are a source of inspiration and of noble dramas. The ignoble ones repeat the same old scenes and the same old plots with the same drab cast, set in the dreary 'catchment areas' which society conveniently supplies as depots where losers can collect their payoffs: saloons, pawnshops, brothels, courtrooms, prisons, state hospitals and morgues…" The following case from hospital practice illustrates the painful stereotypy of such Scripts: Case 2: Suffering for Survival: The Paradox of Self-damage Margaret, aged 23 years, was admitted to hospital after taking her complete stock of antidepressants following a violent and drunken row with her second husband, to whom she had been married for three months. Like her first husband, he either ignores her or hurts her; moments of positive intimacy are nonexistent. Her medical and social history indicate the depth and breadth of her emotional deprivation. Margaret escaped the conflictual relationship with her adopted father at the age of 16 years by becoming pregnant by, and then marrying, a man whose sadism was matched to her reciprocal masochism. Within a year her anger and depression led to her slashing her wrists, which heralded the first of three cacophonous and fruitless admissions to a psychiatric unit. This was followed by three consecutive convictions for bomb hoaxes and one for theft. In each case she deliberately left trails, so that a game of 'Cops and Robbers' could be played with the police before her welcome and inevitable terms of imprisonment ensued. As with hospital, she saw prison as a place of security and punitive care corresponding with her own sense of worthlessness. After prison she was placed in a succession of aftercare hostels, but found these too unstructured and lenient despite her testing-out behaviour. Her medical condition then erupted into a variety of painful physical complaints for which she frequently attended her general practitioner. Overwhelmed, he, in turn, referred her to various hospital departments. In the last three years she sustained four abdominal operations for suspected appendicitis, salpingitis, an ovarian cyst and adhesions. She underwent an extensive series of elaborate investigations for headaches and had two D and Cs for menstrual irregularity. She was admitted to hospital as an emergency with a feigned but suspected pulmonary embolus and was equally convincing to a cardiac arrest team who rushed to an episode of collapse. It may be added that she smokes heavily and has abused a variety of dangerous drugs; if she cannot get others to damage her then she will do it herself. Margaret's Past Margaret knows nothing of her natural parents. In infancy she was adopted by a married couple who had been told that they could not have children, although this was later disproved by the birth of three sons. Her adoptive father was a rigid, domineering man who had contemptuous and controlling attitudes towards women. His wife had wished for children more than he, and it is probable that he adopted Margaret more out of a feeling of grudging duty than any nurturing impulses. Margaret was always criticised, belittled and restricted far more than her adopted brothers, who have not shown her negative and self-damaging traits. Much of the adoptive father's controlling and punitive behaviour towards Margaret may have stemmed from his incestuous feelings towards her; certainly in adolescence this seemed more overt and added to the predominantly negative identity she had formed for herself. Margaret has much warmth, intelligence and capacity for insight. She embarked briefly on psychotherapy and showed disarming understanding of the roots and nature of her problems. However, the acceptance and positive stroking she received from therapy was uncomfortable and unpalatable for her. Her need for pain and punishment was greater, and she soon abandoned therapy in favour of her more practised and habitual self-damage. Her Script is like an 'autopilot' leading her to self-destruction. Only when she takes over the 'manual controls' of her life will she avert the early death she has programmed herself for. The 'Suicidal Spectrum' Suicide in one fell swoop is only one dramatic example of inevitably self-destructive behaviour. In this respect the act of suicide differs only in acuteness and intensity from other patterns of behaviour which damage the self and its relationships with others.5 All of them may be located on a 'suicidal spectrum'. Clear examples of more chronic and common types of self-damage include drug-abuse, alcoholism, obesity, heavy cigarette smoking and dangerous driving. More covert and subtle suicidal equivalents are suggested in chronically unhappy relationships, a propensity to illness requiring surgery, and choosing dangerous types of employment. In all these there is a compulsive tendency towards recurrently hurtful relationships, activities and lifestyles. Such an investment keeps the world predictable in terms of archaic childhood formulations, and provides the kind of strokes that, spuriously, seem bound to security and survival. Case 3, from the setting of general practice, indicates how skilled and timely intervention may help dispel such unconscious but self-damaging patterns of behaviour. Case 3: A Game in Action Miss E. is a healthy, articulate, fabric designer aged 30 years. She attended her general practitioner, Dr F., routinely in his surgery saying she had a dry cough which kept her awake at night. She looked well and a competent history and examination revealed nothing else of significance. Dr F. noted, however, that she seemed surly, challenging, and irritable. When he asked her if there was anything else irritating or upsetting her he got a brusque rebuff. The doctor felt he had to offer something and she left with a prescription for a simple linctus and a platitude of "It's nothing to worry about". Two further appointments at close proximity followed a similar pattern, but Dr F. felt increasingly harassed and impotent. Feeling that he could now only offer her competent, if exhaustive, medicine he pondered the remote possibility of a growth or tuberculosis. The following dialogue then revealed the underlying Game: Dr F: I think you must have a chest x-ray. You've still got this cough and I don't know why. I don't think it's anything serious, but I want to be sure. Miss E: (angry and churlish) Oh, I don't want to go through all that. I just wish you'd get rid of this cough. Dr F: (sharing her irritability) How can I when I'm not sure what it is and you won't cooperate? Miss E: (hurt and put-upon) But I just don't want all that hospital stuff. Dr F: (moving increasingly into a frustrated and controlling (Parent) position and writing out a form) Look, I'd like you to take this form along to St Andrew's and have an x-ray… Miss E: (in an accusatory tone) How do you expect me to go to St Andrew's when I work on the other side of London. I can't just take time off work, you know! Dr F: (trying a stoical and benign last ditch (Nurturing Parent) reconciliation) OK, we'll try and arrange it at St Peter's… Miss E: (overtly peeved, but covertly jubilant) Oh, I'm not going there! Last time I went they kept me waiting hours and they were so rude! Dr F: (now fairly sure of her underlying Game, he pauses and confronts her gently) It seems you don't really want medicine from me. Every suggestion I make is unsatisfactory to you. You seem to be frustrated and angry, but I'm sure it's not really with me. Is there anyone else stopping you doing what you want? Guerrilla Warfare The anger and obstinacy then lifted and were replaced with the hurt and helpless tears of her Child. Miss E. was at an impasse in her life. She was excessively dependent on a father whom she experienced as patriarchal, overprotective and snobbish, and looked to her for the allegiance and affection he did not get from his wife. The pattern over the years was for her to play the role of the flirtatious and doting daughter, and for him to protect her with his role of 'Big Daddy'. Not surprisingly, no real growth or autonomy was possible for her in this system. However, it had worked fairly unremarkably until recent times when she met a man to rival father. Father's wrath and disapproval became evident, all the more so as the man was from a poorer and less educated background. In an effort to maintain his dominant and controlling role, father was attempting to bribe, bully or harass her out of her relationship. Although her Adult knew that she needed to break free from her father, her Child was frightened and confused. At the time of this crisis her Adapted Child was painfully divided between appeasement and rebellion. Part of her wanted to surrender obediently, as she had always done. Another part of her felt angry and resentful, and wanted to retaliate against what she saw as oppression by her father. However, years of conditioning are hard to counter. At this time the nearest she could get to confronting father was to wage a guerrilla war against the doctor and others she saw as authority figures, who she was treating as father surrogates. Like all guerrilla wars, she was fighting it from the one-down position, and the intention was to harass, disorientate, and discomfit her opponent. Such a confrontation is covert, and the under-dog always has the advantage of surprise and choice of territory. Guerrilla warfare does not seek to destroy the opponent (which is impossible) rather to impede him until such time as a more substantial assault can be made. The important point in Miss E.'s communications with Dr F. was that they were duplicit. Her overt Adult said "Please investigate and treat my cough", but her covert Child said "You can't offer me anything. You try and I'll render you powerless". We can represent these messages as shown in Figure 1.

Playing the Game At first, Dr F. responded to her overt message by dealing with her manifest need. In this way he played her game of "Why don't you? …" "Yes, but …”, where every suggestion he made was returned as useless, making him feel confounded and ineffective. This series of transactions is closely analogous to the Child who will not be fed, thereby giving expression to some of its anger, albeit in a passive way. It was only when Dr F. tuned in to Miss E.'s Child signals that he deciphered and stopped playing the Game. Fortunately, he had the time, interest and skill to help Miss E. deal with the problems they uncovered. Quite as important, she was willing to be receptive and candid with her doctor, a component largely outside the doctor's control. She was then able, with Adult insight, to redeploy her energies and go about the painful and frightening business of confronting her father's control and disapproval. Not all patients, of course, are at such a dramatic and clear-cut impasse in their lives when they bring their Games to the doctor. It is also unrealistic to expect such potent and neat results from skilled medical counselling to occur very frequently. However, even when patients are not ready or willing to consider such radical or necessary changes, the doctor may be spared much in the way of feelings of confusion, impotence and undue guilt. The patient, at least, may be spared much unnecessary investigation and treatment and will be deprived of at least one source of aberrant gratification. This will take some momentum out of his Script, if only temporarily. Even when such insight does not produce the radical and widespread changes we would like to see, it does help us to avoid some important hazards. Furthermore, it may be that when such a hiatus is created, the beginning of awareness and Script dissolution can take place. If we can make even small, but timely, contributions to a patient's awareness and autonomy, we may achieve rather more than via the relentless practice of traditional medical skills. References 1. Spitz R, Hospitalism; genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. Psch. Study Child 1945; 1: 53-74. 2. Levine S, Mullins RF, Hormonal influences on brain organization in infant rats. Science 1966; 152: 1585. 3. Skeels HM, Adult status of children with contrasting early life experiences: a follow-up study. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 1966; 31, ser. no. 105. 4. Berne E, What do you say after you say hello? London, Corgi 1972. 5.Zigmond D, Suicide and attempted suicide: its origin and course. Update 1977; 15: 505-515. David Zigmond, MB, CH.B, MRCGP, DPM, is a Psychotherapist at Hammersmith Hospital. Doctors and Patients 15 JANUARY 1982/UPDATE Contents Copyright ©; Dr David Zigmond 1982, 2010 Interested? Many articles exploring similar themes are available via David Zigmond’s home page on www.marco-learningsystems.com David Zigmond would be pleased to receive your FEEDBACK

|